Why America Needs Systems Intelligence to Win the Reindustrialization Era

We can name the bottlenecks to reindustrialization. However, we lack a shared, evidence-based understanding of the system we’re trying to rebuild. This piece explores why reindustrialization requires systems intelligence and how a new approach, Systems Performance Mapping, can preserve and align coalition knowledge towards policy action.

Ethan Copple

10/30/20257 min read

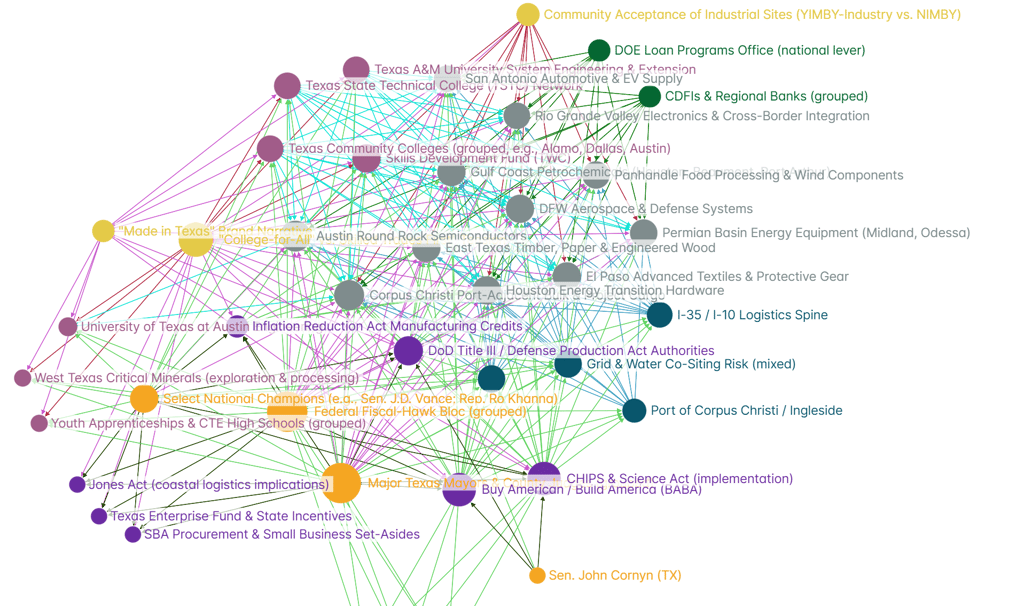

Sample generated graph

For the first time in decades, the United States is serious about rebuilding its industrial capacity. Federal and state governments are pouring billions into semiconductors, advanced manufacturing, clean energy, critical minerals, and defense production. Regional tech hubs are emerging, private capital is mobilizing, and a new ecosystem of organizations is stepping forward to revive American industry. The era of Reindustrialization is ramping up.

This is a historic opportunity. But underneath that momentum is a quieter problem that almost everyone working on the broad issue of reindustrialization has felt: We don’t have a shared, evidence-based picture of how the industrial ecosystem actually works. If you’ve spent any time around people who are trying to build factories, scale manufacturing, stand up supply chains, or shape industrial policy, you’ve probably noticed there’s no shortage of knowledge, capability, or competence. The operators, suppliers, state officials, workforce educators, investors, and policy advocates already know where the bottlenecks are. They can point to the friction, the missing capabilities, the places where promising projects keep dying, and needed investments that are overlooked. Therefore, the issue isn’t insight. It’s the lack of a structured way to prove what insiders already understand in a way that compels action.

Policymakers and funders don’t always move because something “feels true,” even if it is. They need evidence that shows not just what the problems are, but why they exist, how they interact, and which interventions unlock the most progress with the least pain. Without that, even the best ideas struggle to gain traction. This, to me, is the credibility gap in America’s reindustrialization movement. And it’s a gap we can close with something I call Systems Intelligence, built through a method known as Systems Performance Mapping.

Why We Need a Better Lens for Reindustrialization

The reindustrialization challenge isn’t a single-issue problem. It’s not “just” a workforce issue, or a capital issue, or a permitting issue, or a supply chain issue. It’s all of them, interacting at once, in a system shaped by 40 years of offshoring, consolidation, financialization, cultural shifts, and policy drift. After talking with dozens of leaders in the reindustrialization movement, I'm convinced that the main constraint to progress isn’t knowledge. It’s being able to see the system clearly enough to direct efficient change in order to undo decades of errors in a matter of years.

Systems Performance Mapping is a structured way of doing exactly that. It looks at how an ecosystem behaves in the real world, across actors, incentives, institutions, culture, policy, and capacity. It identifies the forces that shape outcomes and reveals the unexpected leverage points that don’t show up if you study problems in isolation. It turns scattered insight into systems intelligence.

What Is Systems Performance Mapping?

Systems Performance Mapping is a way of understanding a complex environment by turning qualitative expertise and insights into a model of how the system works and how to improve it. Rather than studying problems in silos, it looks at their relationships: what amplifies them, what softens them, and where interventions actually stick.

It’s built to answer questions like:

Why aren’t we getting the results we expect, even when we invest in the “right” things?

If we fix this one problem, which others improve as a result? And which don’t?

Where can we act now, versus what requires long-term structural change?

Systems Performance Mapping does this by identifying the factors shaping system performance, mapping how actors and forces interact (including second-order effects), assessing changeability, and pinpointing leverage points where action unlocks real impact. Simply, it turns what experts know into an evidence-based structure.

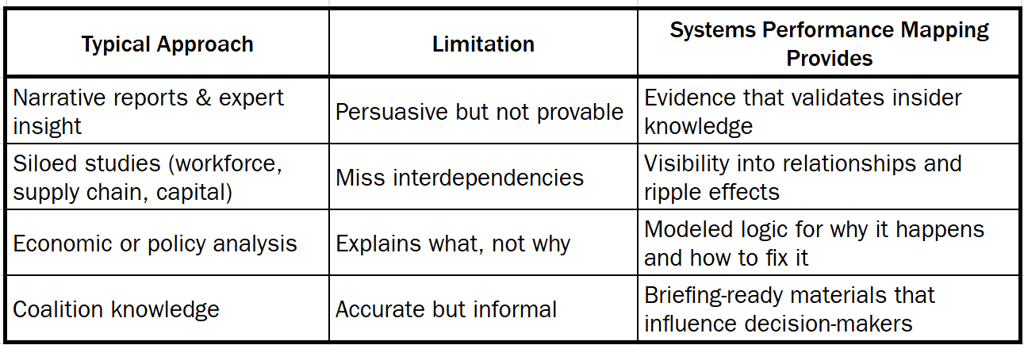

Why This Approach Works Better Than the Status Quo

Most of what exists today in industrial policy research and advocacy is valuable, but incomplete. The table below sums up why:

Simply, rather than relying on mental models or siloed expertise, Systems Performance Mapping creates a shared, evidence-based picture of how the system actually works and where to intervene for the greatest impact.

A Tested Method, Proven at Scale

Before applying this approach to American industry, I spent three years building and iterating the approach inside one of the most complex, politically charged systems you can imagine: the healthcare system of the Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina. The Province is home to over 17 million people, is roughly the geographic size of Arizona, and its healthcare system is a tangled mix of public, private, union-run, and municipal services.

I wanted to understand how the system actually behaved: not in theory, but in lived reality. So I built a methodology that combined qualitative fieldwork with systems modeling. Over 230 interviews from different providers and patients spread across socioeconomic, geographic, and insurance contexts were coded and validated, then translated into network models. I developed new mathematical approaches to see through the network complexity: adaptability scoring, structural complexity analyses, all leading to an intervention roadmap. The result was a picture of the system that no one had seen before: not just what the problems were, but how they interacted, reinforced each other, and could be changed.

Some of the most powerful findings were the ones nobody was looking for. High-impact barriers weren’t always the visible ones. Some small cultural enablers created positive cascading effects across the system. Fragmentation acted as a force multiplier on nearly every barrier. Some issues were highly changeable; others required slow structural reform. Crucially, the work didn’t remain a research exercise. I'm collaborating with administrators began using the findings to guide strategy and policy discussions. The methodology proved itself, not just as theory, but as a tool for decision-makers. If it can bring clarity to a provincial-scale health system, it can bring clarity to the industrial ecosystem of the United States.

Why This Matters for Reindustrialization

Right now, the U.S. feels like it’s in a phase I often describe as “everyone is right, but no one can prove it.” The people closest to rebuilding American industry can all feel the blockages. They can name them, trace them, and point to the patterns that keep showing up in different regions and sectors. Yet because there isn’t a shared model of how the system actually works, these insights remain scattered rather than cumulative. Without that shared view, we unintentionally create competing narratives, fragmented interventions, and a patchwork of local solutions that struggle to scale.

Reindustrialization is fundamentally a systems challenge. It touches workforce, supply chains, financing, infrastructure, regulation, education, culture, and even time horizons and expectations. None of these can be changed in isolation because each reinforces the others. This is why individual policy ideas, no matter how good, are often swallowed by the complexity surrounding them. The system pushes back.

Systems intelligence gives us a way to understand the whole so that we can act on the parts in the right order. It helps explain why problems persist even when we attempt to address them directly. It clarifies which interventions create meaningful downstream improvements, and which only shift the pain elsewhere. It distinguishes the policy levers that actually accelerate change from those that distract or dilute effort. It separates what is ripe for action now from what requires patient rebuilding of capabilities and institutions first.

What Would This Look Like in Practice?

In practice, Systems Performance Modeling is a different way of showing and a different way of accumulating intelligence over time. Picture this: a state manufacturing coalition, a regional tech hub, or a national org like NAIA sits down with the Department of Commerce, a governor’s office, or a key senator. But instead of showing up with yet another static full of recommendations, they walk in with a living model of the industrial ecosystem, something that reflects reality as it’s actually unfolding on the ground. They can show how workforce, capital, suppliers, permitting, culture, and policy interact; where the system reinforces stagnation; and which interventions unlock real movement. This isn’t a one-off analysis. Over time, it turns into a cumulative knowledge asset for the movement.

Because once you have a systems model, you can start to do things that aren’t possible today:

You can stress test policy ideas before burning political capital on them.

You can trace cultural narratives to see how they shape behavior and decision-making.

You can examine where coalitions are naturally aligned or misaligned and adjust strategy accordingly.

You can tailor messaging to different actors because the model shows what each group values.

You can surface the second-order effects of decisions, not just the first-order ones.

Imagine being able to query the system itself:

How would shifting the capital stack or incentives for scale-up manufacturing affect firm survival rates, supplier development, and regional capacity five years out?

How do we change the cultural narrative around vocational education from “Plan B” to a respected professional path?

Which narrative frames or identity cues increase cross-sector cooperation rather than triggering turf protection or institutional defensiveness?

If we introduce a specific policy or intervention, where does resistance emerge, from which actors or institutions, and how will that resistance adapt or mutate as the intervention scales?

And because this model is built with real field intelligence not abstractions, it becomes more accurate every time it’s used. Each pilot adds fidelity. Each region adds nuance. Each conversation with industry, workers, educators, or policymakers enriches the model. Knowledge compounds, rather than disappearing into inboxes and X threads. Over months and years, this becomes a shared intelligence infrastructure for reindustrialization: a way for the movement to remember, learn, adapt, and coordinate. It's how we got from scattered expertise to a national knowledge engine that doesn’t just document complexity, but helps us navigate it.

If We Get This Right

Systems intelligence won’t replace policy expertise, industrial know-how, capital strategy, or community wisdom. Instead, it gives those things a backbone or a structure that holds their value and makes them legible to others. It helps the align the right ideas with the right people at the right time. It gives leaders the visibility to act on the systems as a whole, while not tying that knowledge to a single person or small group. It becomes an institution in itself that adapts with systems changes. If we build this capability, we can stop reinventing the wheel in every region, every sector, every cycle of federal funding. We’ll be able to learn faster than the problems evolve. We’ll remember what worked, and what didn’t, and why. Our interventions will compound rather than scatter. We can continue to compounds wins to create a persistent national capacity to build, adapt, and produce.

We already have a deep belief in the necessity of reindustrialization. Systems Performance Mapping builds a shared, compounding knowledge base. It creates a way to collect, retain, and distribute knowledge across people, organizations, and institutions. It provides the knowledge engine capable of aligning millions of stakeholders and assembling the coordinated will towards the reindustrialization of America.