Restoring a Culture of Community and Hosting

Reflections on building a social life within family life.

Ethan Copple

2/20/20258 min read

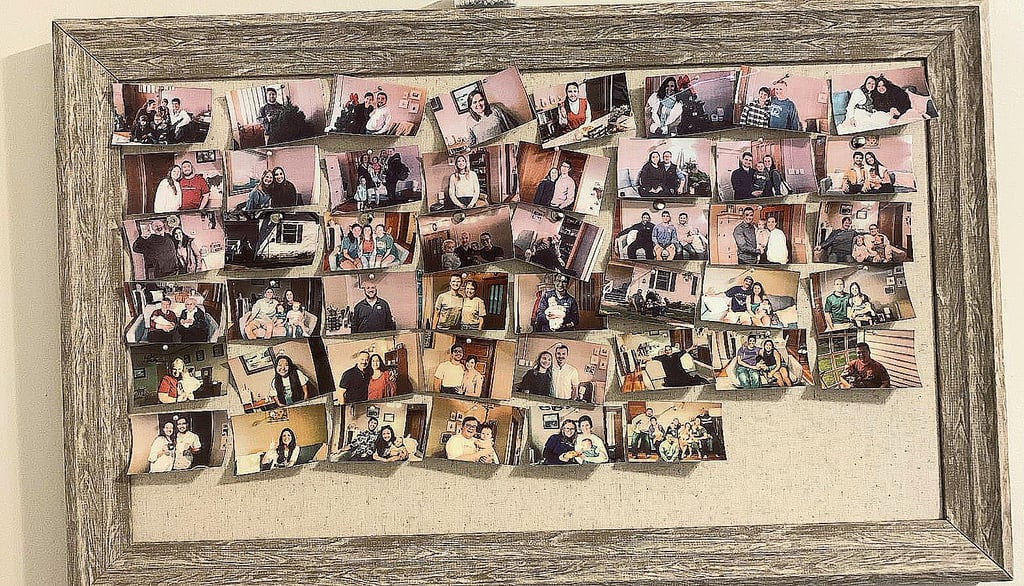

My wife and I live a bit of a different life than most. We're not big TV or Netflix fans - and really haven't watched more than a handful of movies together over the course of our marriage. We often get questions from family about what we 'do every night' if we aren't watching something or even reading. In fact, we don’t even own a TV. We do keep quite busy on an activity that seems to be increasingly deprioritized: hosting. Each week, we host or are hosted between 4-5 times with friends with some busier weeks seeing us spend upwards of 8 meals with others (see the polaroid board from our first few months in Kansas). In the internet and post-pandemic age, this level of social engagement is almost strange - but it's an extremely fulfilling way to live life.

The Trends of Isolation

The book, Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community, highlights these trends that fewer and fewer people host regularly. Robert Putnam highlights that from 1975 to 1999, the frequency of families inviting friends over for dinner declined by 45%. This trend seems to have continued its trajectory beyond the timeline of Putnam's study, though studies that directly examine such trends don't exist. Generally, though socialization times have stabilized, the quantity (and likely quality) of face-to-face time has decreased significantly from the early 2000's to now (WBUR). When comparing demographics, such as age, the change can be even starker. Teenagers have seen drops of nearly 50% of face-to-face time. The trend, starting in the 1970's then further accelerated in the mid-2010's, likely being driven by cell phone proliferation. This trend towards isolation is correlated with skyrocketing rates of depression, anxiety, and hopelessness.

But, that's enough context. Unfortunately, most of us have anecdotal and observational experiences that solidify these numbers and the trend towards isolation in addition to the mountain of articles and research that confirm these changes.

A 'Social' Family

It's the summer of 2020 in Wichita, Kansas. I had the gift of living with my Godparents for several months while I interned at an aerospace manufacturing company. They're a pretty normal family - a hospital administrator and a school teacher with a few kids. But what struck me that summer was how often they hosted or were hosted. Their house was constantly full with the coming and going of friends and family - sometimes with multiple sets coming by throughout the evening. During the midweek, each week, a group of their extended family and family friends (often 20+ people) gathered to share a meal and relax through the evening. After a family-style meal with several bottles of wine, the men caught up amidst the tosses of bocce balls and women chatted on the couches. It was a 'Saturday night' in the middle of the week.

A 'Normal' Family

This level of socialization was a new phenomena to me. I had a pretty standard experience growing up with nuclear family-centered dinners. There were occasional parties or invitations to other's houses, but there was a certain formality about it. Further, my family lacked close family friends with my parents becoming cordial acquaintances with the parents of my and my sibling’s friends. Thus, we were content at the time to partake in family dinners.

Another observation I made in my adolescence was the lack of new friends I saw my parents make. My parents had work acquaintances and neighbors, but rarely sought to spend time with them outside of formal contexts like holiday parties. They maintained contact with friendships established in college but we rarely, if ever saw them.

Now all of this is reasonably normal, if not expected in our society today. There's always been a sense of college as the 'glory days' and the time of the most socialization that you’ll ever have in life. However, this concept has never sat right with me.

There are family commitments, kid's activities, work, and ever growing lists of home chores - but I always wondered why social lives seemingly fizzled out at the end of college and if that could be avoided. With my Godparents, I had found an apparent answer.

Chartering a Path for My Social Family

In my dorms and houses at university, there was always a constant stream of social events, people coming over, or nights on the town. It would be easy to see how the shift into a new city, new job, and new life after college would stunt that ever enjoyable aspect of life. I was curious if there was a way to keep this spontaneous activity alive after university - keeping that flow of people in and out of our home.

Simply, I knew that I wanted something different for my social life and family after university. However, there were few theoretical or practical models. Through my later years of college, I read a number of books to deepen my understanding of the social crisis; however, I was struck by the lack of solutions presented.

Beyond my experiences with my Godparents, I also discovered a sort of model in the book Live Not By Lies. Dreher describes the Benda house in the midst of the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia, where the home became a center of activity, hosting lectures, informal dinners, and religious formations. Now obviously, the conditions in the U.S. differ immensely from those in 1970’s Czechoslovakia; however, the idea of the home being a center of activity, learning, community, and formation interested me greatly.

Refounding Community in an Isolated World

Early into dating my now wife, I outlined my desire to have some form of social engagement be a priority of my life and home in the future. I recognized the reality that socialization and community are not natural outcomes in our modern society. Community and friendships need to be built - they need to be invested in - they need to be prioritized. Practically, this means a stated, planned, and executed prioritization of time and resources to building a community.

There are a number of things that help facilitate the building of a community - ‘infrastructures’ if you will. These can take a number of forms and range from physical city design to cultural expectations of hosting. Clearly, there’s also going to be a spread in what can be reasonably impacted by an individual or group of individuals. A common complaint I’ve heard with hosting is that ‘everything needs to be perfect,’ conjuring images of their moms making them dust baseboards before guests arrive. The most potent infrastructure I’ve come across in supporting a vibrant community and normalizing hosting is the destruction of this cultural idea.

Things do not need to be perfect, perfectly clean, nor perfectly presented in order to host. Especially with our toddler daughter now, our house will rarely, if ever, be able to measure up to this standard. Thus, by hosting when things aren’t perfect, not denigrating the fact that our daughter plays and things aren’t perfectly clean, and messaging that we don’t expect other peoples’ houses to be perfect, we are able to facilitate reciprocity in hosting. Lowering the bar of hosting expectations has been a key to successfully encouraging others to host. When you are able to model low-stress hosting, it invites the others to drop these concerns for perfection as well.

The next key ‘infrastructure’ is committing to consistency within relationships to cultivate actual friendships. There are rare, instantaneous friendships; however, the vast majority require effort and particularly time. In today’s busyness culture, it can be difficult to carve out the time to be consistent yourself, much less create this reciprocal desire for consistency.

Using ‘Ferraro Nights’ to Kick-Start a Culture of Local Community

Thus, my wife and I have started a series of groups in the different cities we have lived in. The plan is theoretically simple but requires substantial buy-in to execute. After a few months of sporadic hosting, identifying friendships we’d like to build, and establishing a baseline relationship with another family, we formally invite them to join our group, named Ferraro Nights. We’ll get to the invitation in a bit. First, a description of how we structure the nights.

Ferraro Nights consist of two parts: a shared, family style dinner with time for fellowship and a formation hour where the hosting family presents a topic, question, or activity. Our Ferraro Nights are specifically structured to build up relationships with other Catholics in our parish, so our formations are generally focused on theological formations; however, we also discuss questions related to how we plan to raise our kids, timely cultural or political occurrences, and other faith-tangential topics. This two part approach is key to building a general friendship and knowledge of the other (fellowship) while also building deeper connections through discussions of greater substance (formation). Each week, the families take turns hosting and leading formation, rotating responsibility to each family throughout the month. This in turn becomes a vehicle to ‘teach’ others to host and create a culture of deep community. Notably, after starting Ferraro Nights, most participants start hosting others outside of the immediate group more often, likely a fruit of the culture and confidence participating in a Ferraro Night creates.

In order to join a Ferraro Night group, we make a fairly formal invitation to other families. This consists of us hosting them for a dinner, sharing our testimonies about how community has improved our lives and commitment to our Church, and sharing an initial letter. This letter restates bits of our pitch and states expectations we have for them participating in the group. Namely, we ask them to commit to attending weekly dinners 80% of the time for a year. Weekly dinners help drive the consistency needed to build relationships quickly. 80% of the time clarifies that attending the dinners is not optional week to week - if you are traveling or sick, it’s okay. But, otherwise we need you at this dinner to have that consistency with others. Lastly, committing to a year demonstrates that this is a group that will have consistency for a sufficient amount of time to develop the foundation of a deep community.

After receiving the formal invitation, we invite all the families together to a cocktail night where we flesh out details about when, how, and why we are going to have Ferraro Nights. The other families are able to meet each other, ask questions, and get a sense of what a weeknight together could look like. From there, we ask for commitments from the families and start our weekly nights. My family will host the first month or so to model hosting, set the pace for the evening, build confidence in other families, and demonstrate different ways to lead formation.

The How and Why?

I’ll be writing a separate piece that dives into the specifics and practicals of hosting. However, I wanted this piece to describe the barriers to hosting, the community crisis and my thought process in developing a culture of hosting in my own family and local community.

Fundamentally, building a culture of community isn’t something that happens passively—it requires intentionality, commitment, and consistency. In a world where busyness and digital interactions have replaced deep, face-to-face connections, we have to actively resist the inertia of isolation. By prioritizing time and resources for consistent social engagement, dismantling the perfectionist mindset that keeps people from hosting, and modeling a low-stress, reciprocal approach, we can create friendships and real community. What started as a simple desire to maintain the organic social life of high-school and college has become an intentional effort to redefine what it means to cultivate community as an adult. The reality is that friendships don’t just happen—they are built, nurtured, and sustained by people who choose to show up, week after week, year after year. And when we commit to this, we’re not just making our own lives richer—we’re contributing to something much bigger: a countercultural movement that reclaims the home as a place of connection, formation, and belonging.