Industrial Policy Series: The Jones Act or Merchant Marine Act of 1920

Ethan Copple with help from Generative AI

3/4/202519 min read

This article is the first in a series that seeks to summarize (in long-form content) key industrial policies impacting the U.S.'s industrial policy. The goal is to provide an overview of the importance of the policy—tying it to critical debates surrounding national security and policy reform, while also highlighting key stakeholder desires and how they could be overcome in reform.

Introduction

The Jones Act—officially the Merchant Marine Act of 1920—has shaped U.S. maritime policy for over a century. Originally designed to strengthen the domestic shipbuilding industry, ensure a reliable merchant fleet, and secure logistical capacity for wartime needs, it remains one of the most fiercely debated pieces of trade legislation in the country. It’s impacts stretch to wartime readiness, supply chain resilience, and other topical issues.

Supporters argue the Act safeguards national security, protects American jobs, and ensures the U.S. retains a viable commercial fleet. Critics counter that it artificially inflates shipping costs, limits economic competitiveness, and is increasingly misaligned with modern supply chain realities.

But to understand its full impact—both intended and unintended—we need to examine how it has shaped domestic maritime trade, influenced wartime logistics, and introduced vulnerabilities in cybersecurity, energy, and broader transportation infrastructure.

Understanding How Policy Impacts

As a Kansas-born, plains and heartland raised man, the Jones Act was never a policy I’d heard about until I started diving into the U.S. Navy procurement issues with the Zumwalt, LCS, and now Constellation class Frigates. Amidst the reports of late deliveries, production issues, and constantly changing requirements, there were occasional mentions of the impacts of the ‘Jones Act’ and trade policies post-WWII on current shipbuilding capacity and capability. It’s further come to a head in my involvement with the Reindustrialize movement. At the first conference in June 2024, there were no fewer than 3 debates, panels, and discussions surrounding the Jones Act and more general maritime policy.

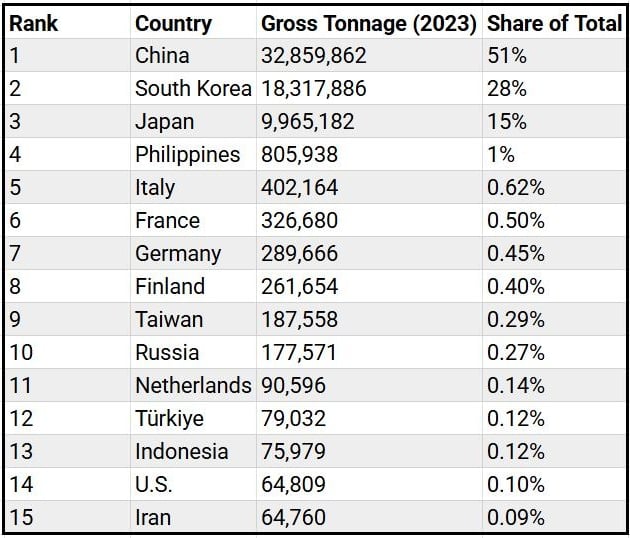

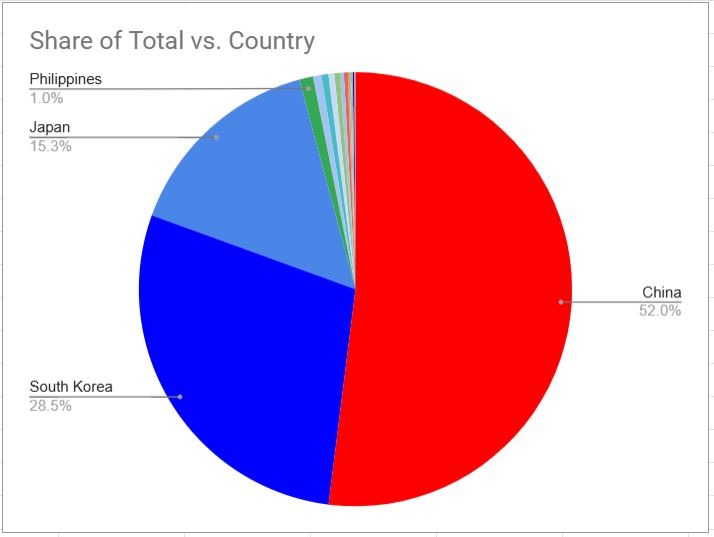

The mentioned concepts of capacity and capability are key in shipbuilding. For instance, Italy, a close NATO ally, has sufficient shipbuilding capability, though lacks capacity to produce large quantities of warships or otherwise. Note the table below with approximate shipbuilding market share in terms of gross tonnage (i.e., the summed size of the total number of ships). Now, this table and chart excludes military vessels, yachts, fishing vessels, offshore platforms, and barges as it’s from the U.N. Trade and Development’s data; however, it still paints a concerning picture of both capacity and capability. The chart further demonstrates this by highlighting US-aligned nations in shades of blue, non-U.S. aligned nations in red, and more neutral nations in green.

The U.S., once the predominant shipping power and producer now sits outside of the Top 10. Notably, China, a key geopolitical rival in the Pacific, has taken a lion’s share of shipping capacity. South Korea and Japan, close U.S. allies, are quite far behind, considered individually. Due to the time to construct shipbuilding facilities and the large ships within them, a conflict would likely be long over before wartime investments by the U.S. or other allies would boost this capacity. This all, ultimately, leads the U.S. and U.S.-aligned nations being woefully unprepared for future conflicts and to maintain control of global trade. China, South Korea, and Japan also all heavily subsidize their shipbuilding industries as part of their national interest and defense policies. These subsidies along with more modern shipbuilding techniques and labor arbitrages allow for these nations to drastically reduce costs to produce ships compared to the U.S.

Now, the Jones Act alone is not responsible for the state of U.S. shipbuilding; however, it certainly influences it and reforms (or lack thereof) will impact the competitiveness, capacity, and capability well into the future.

Why the Jones Act Exists

The origins of the Jones Act are deeply rooted in the tumultuous early decades of the 20th century, when the United States was rapidly emerging as a global power. In the wake of World War I, the vulnerability of relying on foreign shipping became starkly apparent. American policymakers recognized that if the nation were ever drawn into another conflict, it could not afford to be dependent on foreign vessels or shipbuilders—risks that could compromise national security and disrupt vital supply chains. This realization was the driving force behind the passage of the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, popularly known as the Jones Act.

The Jones Act imposed four key restrictions on vessels engaged in coastwise or intra-national trade (i.e., shipping between U.S. ports):

Ships must be built in the U.S.

Ships must be owned by U.S. citizens or entities.

Ships must be at least 75% crewed by U.S. citizens.

Ships must be registered under the U.S. flag.

At its core, the Jones Act was designed to ensure that the United States maintained a robust domestic maritime industry capable of meeting both commercial and military needs. By mandating that all goods transported by water between U.S. ports be carried on vessels built in the United States, owned by U.S. citizens, and crewed predominantly by Americans, the Act was intended to:

Bolster National Security: In an era of growing international tensions, a sovereign fleet was seen as essential for quickly mobilizing resources during emergencies. The belief was that a self-reliant maritime industry would provide the logistical backbone necessary for sustaining military operations without relying on potentially unreliable foreign carriers.

Protect Domestic Industries: The Act was also a protective measure for the U.S. shipbuilding industry, which was still in its developmental phase. By limiting competition from foreign-built ships, the Jones Act created a captive market for American shipyards. This protection helped to preserve domestic jobs and foster a skilled maritime workforce, laying the groundwork for a robust national infrastructure.

Promote Economic Stability: Beyond its security implications, the Jones Act was envisioned as a way to stabilize and nurture the domestic shipping sector. By insulating U.S. ports and coastal commerce from international market fluctuations, the Act aimed to ensure that vital domestic trade routes remained reliable and economically viable. This was particularly important in an era when international shipping was less standardized and subject to significant geopolitical uncertainties.

The broader historical context cannot be overstated. The devastation of World War I had exposed the weaknesses in global supply chains, and there was a widespread belief that the future of American prosperity and security depended on self-sufficiency. The Jones Act emerged as part of a broader movement toward protectionism in the interwar period—a time when nations were increasingly focused on safeguarding their domestic industries from foreign competition.

Moreover, the strategic rationale extended beyond mere economic protection. Lawmakers foresaw that a robust merchant marine would serve as a crucial reserve force during times of military conflict, providing a ready pool of ships and trained crews that could be quickly mobilized. In effect, the Jones Act was not just an economic policy, but a strategic investment in national resilience.

While the Act was conceived nearly a century ago, its underlying purpose—to secure a sovereign maritime capability—remains a central pillar of American national security doctrine. However, as will be discussed later, there is rising criticism surrounding the effectiveness of the Act in both commerce and national defense.

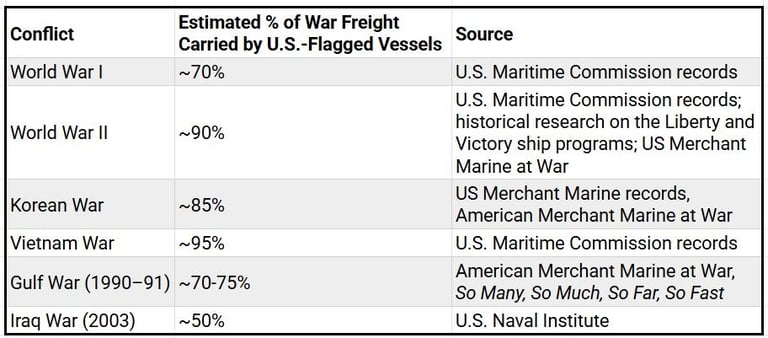

U.S.-Flagged Vessels in Wartime: A Declining Role

As noted, a key rationale for the Jones Act was to give the U.S. sufficient sealift capability to transport its armed forces across the ocean and to act as a quickly-mobilized reserve of transport ships in wartime. Thus, understanding the role of Jones Act compliant vessels in U.S. conflicts is important to understand the risks that current shortcomings of U.S. shipbuilding present.

World War I: Laying the Foundation for Maritime Self-Sufficiency

Before the Jones Act, during World War I (1917-1918), the U.S. quickly realized the dangers of relying on foreign shipping for military logistics. At the start of the war, the U.S.-flagged fleet was relatively small, and much of the country’s trade was carried on foreign, primarily, British vessels. However, by the war's end, the US merchant marine expanded significantly. Research indicates that approximately 70% of cargo transported in support of the war effort was carried by US-flagged ships, based on the growth from 1,500 to over 4,000 ships and the context of allied shipping reliance (estimation based on historical context). This figure reflects the early stages of US maritime expansion, with some uncertainty due to limited specific data. The experience highlighted the need for a strong domestic maritime industry, laying the groundwork for the passage of the Jones Act in 1920.

World War II: The Height of U.S. Maritime Dominance

World War II (1941-1945) marked the peak of American shipbuilding and merchant marine capacity. With an all-out industrial mobilization, U.S. shipyards produced over 2,700 Liberty and Victory ships, drastically expanding the U.S.-flagged fleet. American merchant ships carried nearly 270 million tons of cargo between 1941 and 1945, accounting for about 90% of the total war-related cargo. This high percentage reflects the US's dominant role in global logistics during the war, with minimal reliance on foreign-flagged ships.

Korean War: A Still-Strong, But Aging Fleet

By the time of the Korean War (1950-1953), the U.S. merchant marine remained formidable, though much of its fleet consisted of ships built during World War II. U.S.-flagged vessels carried 85% of military cargo to the Korean Peninsula, with the Military Sea Transportation Service (MSTS) chartering ships to support UN forces. However, the conflict also revealed the first signs of decline. Many of the wartime-built vessels were aging WWII Victory ships, and U.S. shipbuilding was no longer operating at its wartime peak.

Vietnam War: The Beginning of Decline

The Vietnam War (1955-1975), the US merchant marine played a critical role in sealift operations. At least 172 National Defense Reserve Fleet (NDRF) ships were activated, and together with other US-flagged merchant vessels, they carried 95% of the supplies used by the American armed forces. This high percentage indicates near-total reliance on US-flagged ships for military logistics, with MARAD reports confirming the activation of World War II-era Victory ships for this purpose. Clearly, though still being able to rely on U.S. flagged ships, the merchant marine fleet was becoming increasingly aged.

Gulf War: Foreign Reliance Becomes Evident

By the time of the Gulf War (1990-1991), the decline of the U.S. merchant fleet was undeniable. Analysis of the list of chartered ships shows approximately 70 US-flagged ships and 30 foreign-flagged ships, suggesting that US-flagged ships carried about 70-75% of the cargo, based on a rough estimate assuming similar capacities; however, there is not clear data on tonnage. This decline from earlier wars reflects growing reliance on foreign shipping. The Ready Reserve Fleet, a collection of government-owned ships activated during conflicts, played a crucial role in the war effort, but delays in mobilization highlighted the risks of an aging, underfunded maritime industry.

Iraq War: A New Reality of Outsourcing

By the time of the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, the use of foreign-flagged vessels for military logistics had become routine. U.S.-flagged ships transported only 50% of war freight, with the Department of Defense increasingly relying on commercial foreign carriers and international shipping agreements. The decline in American merchant marine capacity had direct implications for national security, as the military was now dependent on foreign-owned ships to sustain operations abroad.

Modern Unintended Consequences

While the Jones Act was originally designed to secure national maritime self-sufficiency, its effects have spilled over into many modern sectors, creating challenges that go well beyond shipping costs or U.S. wartime readiness.

Cybersecurity & Supply Chain Risks

Many U.S.-flagged vessels subject to the Jones Act are aging, and as a result, they often rely on outdated digital infrastructure. This legacy technology leaves them especially vulnerable to cyberattacks—a breach could compromise critical systems and disrupt entire domestic shipping routes. With the U.S. fleet limited in number, the risk is magnified: a cyber incident targeting just a handful of these vessels could lead to significant delays and losses in the supply chain. Moreover, the sector’s chronic underinvestment in digital resilience means that modern logistics technology is slow to be adopted, leaving the fleet less prepared to fend off increasingly sophisticated cyber threats. This vulnerability not only endangers commercial operations but also poses a national security risk by potentially interrupting vital military supply lines or targeting key river and port infrastructures.

Environmental Costs: An Unintended Barrier

The Jones Act’s stringent requirements not only raise shipping costs but also drive up emissions by forcing companies to adopt less efficient transport methods. With a limited pool of U.S.-flagged vessels available for domestic routes, many companies must shift cargo to alternative modes such as trucking and rail. These options are typically less fuel-efficient and produce higher greenhouse gas emissions, undermining broader environmental sustainability efforts. This inefficiency in the transportation network has far-reaching implications, especially for the renewable energy sector.

In the offshore wind industry, for example, there is a significant shortage of Jones Act-compliant vessels capable of handling the specialized installation of massive wind turbine components. As a result, companies are compelled to rely on expensive foreign-flagged ships, which are not allowed to transport components between U.S. ports. This not only causes delays in project timelines but also escalates overall costs, hindering the pace of renewable energy deployment. Similarly, the transportation of green hydrogen—a promising yet logistically challenging clean energy carrier—is hampered by the limitations of the current domestic shipping framework. The complexities and higher costs associated with moving green hydrogen by sea under the Jones Act further complicate efforts to integrate this energy source into the domestic market, ultimately slowing the nation’s transition to sustainable energy.

A Shadow Subsidy for Trucking & Rail

Because Jones Act shipping is often prohibitively expensive, many companies are compelled to shift their freight onto trucking and rail networks, even when maritime transport might be the most efficient alternative. This redirection of cargo increases highway congestion and elevates emissions, while also creating an unintended subsidy for the overburdened trucking and rail sectors. As these transportation modes absorb more freight, public resources are stretched thin and the environmental impact grows. The resulting imbalance distorts the competitive landscape and leads to a less efficient overall transportation system, undermining the potential benefits of a diverse and balanced national logistics network.

Increased Shipping Costs for U.S. Territories and States

Another significant consequence of the Jones Act is the elevated shipping costs experienced by U.S. territories and non-contiguous states such as Puerto Rico, Alaska, and Hawaii. These regions rely heavily on maritime transport due to their geographic isolation, and the Act’s restrictive framework limits the number of vessels available for domestic routes. With fewer options and higher operating costs for Jones Act-compliant ships, the cost of moving goods increases considerably. These higher shipping expenses are ultimately passed on to consumers and local businesses, hampering economic growth and reducing the competitiveness of these regions. The burden of elevated costs not only affects everyday commerce but also poses challenges for emergency logistics and long-term infrastructure planning in these critical areas.

Military Recruitment & Readiness: Fewer Mariners, Bigger Problems

The decline in the U.S.-flagged fleet has not only economic and logistical implications—it also directly impacts national defense. Fewer domestic vessels mean there are fewer job opportunities for American merchant mariners, a critical talent pool that supports naval logistics and auxiliary operations during times of crisis. As the number of trained mariners shrinks, so does the nation's capacity to rapidly mobilize a robust maritime workforce in emergencies. This contraction poses a serious challenge to military readiness: if the U.S. were to engage in a large-scale conflict requiring sustained logistical support, the current pool of skilled mariners might fall short of demand. In this way, the unintended consequence of a limited domestic fleet is a potential vulnerability in the country’s ability to maintain a secure and effective maritime support structure in times of war.

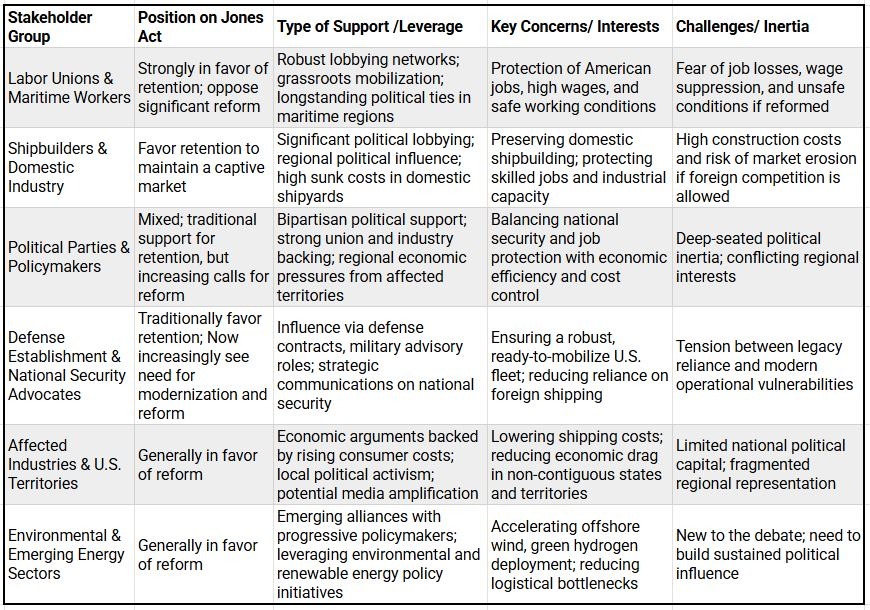

Stakeholder Landscape: Key Players and Their Positions

The Act has had extremely limited reforms, often in the form of temporary waivers or minor clarifications, since its induction in 1920. With the noted issues and limitations surrounding the Jones Act, there is a growing desire to introduce some type of reform; however, this would require substantial political will. Notably, there are large numbers stakeholder groups, often with outsized political power, that influence hypothetical Jones Act reform and maritime policy on the whole.

Labor Unions and Maritime Workers

Labor unions—such as the Seafarers International Union of North America (SIUNA) and other maritime worker associations—are among the most ardent defenders of the Jones Act. They argue that the legislation is essential to protecting American jobs, maintaining high wage and safety standards, and preventing a race to the bottom in labor conditions. Their leverage is significant: unions have longstanding political relationships in maritime and industrial districts, effective grassroots mobilization, and consistent lobbying efforts that have helped cement bipartisan support for the Act. Their primary concern is that any relaxation of Jones Act provisions could lead to job losses, wage suppression, and unsafe working conditions as foreign competition enters domestic waters.

Shipbuilders and the Domestic Industry

U.S. shipbuilders and the broader domestic maritime industry have long relied on the Jones Act to secure a captive market for their high-cost, high-quality products. American shipyards—despite operating at considerably higher construction costs compared to international competitors—benefit from reduced competition and predictable demand. This group exerts influence through strong lobbying and deep ties to local and national political figures in coastal states. Their concern is that reform or repeal of the Jones Act could lead to an influx of cheaper, foreign-built vessels, undermining domestic production, eroding skilled jobs, and eventually leading to a decline in the nation’s shipbuilding capability.

Political Parties and Policymakers

The Jones Act enjoys a complex, bipartisan political backing. Many Democrats emphasize the Act’s role in protecting American labor and fostering industrial stability, while a significant number of Republicans champion it as a critical element of national security. However, rising concerns over inflated shipping costs, particularly in regions like Puerto Rico, Alaska, and Hawaii, and issues surrounding sealift and wartime readiness have pushed some policymakers to consider reform. The dual pressures of union lobbying and regional economic pain create a dynamic tug-of-war in Congress, where political inertia often sustains the status quo despite mounting calls for change.

Defense Establishment and National Security Advocates

Within the defense community, the Jones Act was traditionally seen as a strategic asset. Proponents within the military argue that a sovereign fleet is crucial for ensuring rapid mobilization and secure supply lines during conflicts. Yet, operational realities have exposed vulnerabilities: the shrinking and aging U.S.-flagged fleet has, in some instances, forced the Department of Defense to rely on foreign carriers, thereby undermining the Act’s original intent. This tension creates an opening for reform advocates to push for modernization measures—such as updating cybersecurity protocols and incentivizing fleet renewal—while many in the defense establishment still caution against any reform that might further diminish domestic capacity during crises.

Affected Industries and U.S. Territories

Industries in U.S. territories and non-contiguous states like Puerto Rico, Alaska, and Hawaii are among the most vocally critical of the Jones Act. These regions depend almost entirely on maritime shipping for essential goods, and the restrictive framework of the Act often results in significantly higher transportation costs. Although their political capital is relatively limited compared to well-organized maritime unions or domestic shipbuilders, their economic arguments—backed by rising consumer prices and hindered economic growth—have started to gain traction. Their support for reform is driven by the urgent need to reduce logistical costs and improve competitiveness, even though this group sometimes struggles to organize effectively on a national scale.

Environmental and Emerging Energy Sectors

A diverse coalition of renewable energy and environmental advocates has recently emerged as a critic of the Jones Act. They contend that the Act's strict vessel requirements not only create bottlenecks and delay the deployment of clean energy projects—such as offshore wind farms and green hydrogen initiatives—but also force companies to rely on less efficient transportation alternatives. These alternatives often result in higher greenhouse gas emissions compared to more efficient maritime shipping options, undermining broader environmental goals. Although these groups lack the historical political capital of traditional maritime stakeholders, their influence is growing rapidly as the nation grapples with climate change and seeks to diversify its energy infrastructure. They are calling for targeted exemptions or reforms that would allow for the use of non-Jones Act vessels in environmentally critical projects, thereby reducing emissions and accelerating the transition to sustainable energy sources.

Summary Table: Stakeholder Groups and Their Positions on the Jones Act

Rethinking the Jones Act: Arguments for and Against Reform

The Jones Act was forged in a very different era—a time when ensuring a self-reliant domestic maritime industry was essential to national security and economic independence. However, in today’s globalized economy and rapidly evolving defense landscape, many argue that the Act’s protectionist framework is outdated. While some contend that the policy must be overhauled to better align with modern realities, others believe that its core principles remain vital for safeguarding U.S. interests. The following presents key arguments from both sides.

Arguments and Concepts for Reform

U.S. Shipbuilding and operational capacity and capability shortcomings – The U.S. has not been able to maintain self-sufficiency or global leadership in maritime or construction.

Allow U.S.-owned but foreign-built ships to operate domestically – Reducing construction costs would increase the number of Jones Act-compliant vessels.

Grant case-by-case exemptions – Essential industries like offshore wind could benefit from targeted waivers rather than being forced into costly workarounds.

Modernize cybersecurity requirements – Upgrading digital infrastructure should be a priority, particularly given the vulnerability of aging vessels to cyber threats.

Reassess its impact on national security – If the Act is failing at its primary goal—ensuring a strong U.S. merchant fleet for wartime logistics—it’s worth reconsidering whether its current structure makes sense.

Ultimately, the arguments and concepts for reform are best summarized by the concepts highlighted at the start of this article: Capability and Capacity. Due to changes in global competition, the U.S. now lacks both shipbuilding and operational capabilities and capacities. Even with greater clarity on these shortcomings and geopolitical jockeying with China, little, substantive change has occurred due to Jones Act requirements.

Advocates for reform argue that modernizing the Jones Act is not only economically sensible but also essential for national security in the 21st century. One of the most compelling proposals is to permit U.S.-owned but foreign-built vessels to operate domestically. Global shipbuilding costs are significantly lower than those in the United States—often by a factor of four or five. Allowing foreign-built ships under U.S. ownership would expand the fleet quickly and cost-effectively, ensuring that essential maritime capacity is available without the burden of unsustainable domestic construction expenses.

Furthermore, reformers contend that the current “one-size-fits-all” approach of the Jones Act stifles innovation in critical sectors. For instance, the renewable energy industry, particularly offshore wind and green hydrogen, has been hampered by a dearth of compliant vessels. Targeted exemptions or temporary waivers for these sectors would remove bottlenecks and foster a smoother transition to a sustainable energy future. Such reforms would not only lower costs but also accelerate progress on national energy goals, making the country more resilient in the face of global environmental challenges.

Modernizing cybersecurity requirements is another cornerstone of the reform agenda. Many U.S.-flagged vessels operate on antiquated digital systems that are highly susceptible to cyberattacks. These vulnerabilities can have cascading effects across domestic supply chains and even national defense logistics. By mandating updated cybersecurity standards and incentivizing investments in modern digital infrastructure, policymakers can dramatically reduce these vulnerabilities and incentivize modernization efforts. This approach ensures the robustness of the U.S. merchant fleet against digital threats.

Finally, reform advocates argue that the overall impact of the Jones Act on national security must be reexamined. If the Act, originally intended to secure a reliable maritime logistics backbone for wartime operations, now contributes to a diminished U.S. fleet and higher dependency on foreign shipping, then its current structure may be counterproductive. Reassessing its national security merits could lead to a more flexible, resilient policy framework—one that balances the need for a strong domestic presence with the efficiencies of global maritime competition.

Arguments for Retention

National security and wartime readiness – The principle of maintaining a domestic fleet remains valid, even if the execution needs adjustment.

Preserving shipbuilding jobs – A repeal could accelerate the decline of U.S. shipyards and maritime employment if not matched with policy changes.

Avoiding dependence on foreign shipping – A fully open market could leave the U.S. vulnerable to supply chain disruptions in times of crisis.

Opponents of reform emphasize that the Jones Act remains a critical safeguard for national security and the domestic economy, despite its imperfections. They argue that maintaining a baseline of U.S. control over domestic shipping is paramount, particularly during times of geopolitical turmoil. A robust, American-controlled fleet acts as a bulwark against potential supply chain disruptions or foreign actors near critical infrastructures, ensuring that in times of crisis the nation is not forced to rely on unpredictable or antagonistic foreign carriers whose interests may not align with those of the United States.

Retention supporters also highlight the importance of preserving American shipbuilding and maritime jobs. The Jones Act has long been a cornerstone of U.S. industrial policy, supporting an entire ecosystem of shipyards, maritime services, and related industries. Even if U.S. shipbuilding is more expensive, it provides high-quality, secure jobs that are integral to national defense and economic stability. Dismantling or significantly altering the Act could accelerate the decline of domestic shipyards, eroding not only current capabilities but also the specialized skills and technological know-how that would be extremely difficult to rebuild in an emergency. Thus, reform would need to include policy and other guarantees to ensure the competitiveness of U.S. shipbuilders.

Another central argument is that reliance on foreign-flagged vessels exposes the United States to significant risks. A fully open domestic shipping market might lead to a proliferation of foreign carriers operating within U.S. waters. This could increase vulnerabilities related to espionage, smuggling, or even coercive economic practices by nations with competing strategic interests. Maintaining the Jones Act, therefore, ensures that critical infrastructure remains under American oversight—a vital factor in preserving both economic independence and national security.

Finally, proponents of retention argue that the Jones Act serves as a deterrent to foreign interference. In an era marked by complex global power dynamics, having a sovereign fleet is not merely a matter of economic policy but a strategic imperative. The presence of a U.S.-flagged fleet provides a tangible signal of national resolve and self-reliance, qualities that are indispensable in maintaining both domestic confidence and international credibility.

Conclusion

The Jones Act, a cornerstone of U.S. maritime policy since 1920, was designed to protect American shipbuilders and ensure a robust domestic merchant marine for national defense. However, the current framework has increasingly shown its limitations. In today's competitive global environment, our shipbuilding industry faces significant disadvantages—particularly when foreign nations heavily subsidize their shipyards, creating an uneven playing field. To level the market, we must consider adopting a dollar-for-dollar subsidy program for U.S. shipbuilders. This approach would allow American shipyards to compete fairly without completely insulating them from market pressures, thereby maintaining the benefits of competition while ensuring that our domestic capacity is not undermined.

Furthermore, the core promise of the Jones Act—to build and sustain a capable U.S. merchant marine—has not been met. Despite its intentions, our domestic fleet has steadily declined in both size and modernity. This erosion of capability is particularly alarming in the context of a rising strategic rivalry with China. In a hypothetical conflict, the inability to rapidly mobilize a modern and sizable merchant fleet could severely compromise U.S. national security and ability to sustain itself and allies across the Pacific. It is imperative, therefore, to reform the Act in ways that reinvigorate shipbuilding and modernize operational practices, ensuring that our maritime logistics can meet future challenges.

Balancing the diverse interests of key stakeholders will be essential to any successful reform effort. Labor unions, which have long championed the Jones Act as a protector of American jobs, must be brought into the reform process. By integrating robust wage, safety, and training provisions, we can secure union support while also introducing competitive elements that drive efficiency and modernization. Additionally, engaging defense officials and maritime industry leaders is crucial to ensure that reform measures not only boost economic performance but also reinforce our national security posture.

Ultimately, reforming the Jones Act must deliver a clear pathway to enhanced domestic shipbuilding and operational capacity. By instituting targeted subsidies, modernizing regulatory requirements, and offering flexible, performance-based criteria, we can transform the U.S. maritime sector into a dynamic, competitive, and strategically resilient industry. Such changes will ensure that American shipyards can invest in new technologies, expand capacity, and sustain a merchant marine capable of meeting both economic and defense needs in the 21st century. Reforming—or at least modernizing—the Jones Act doesn’t mean abandoning its core goals. A policy designed to protect American shipping should ensure that the U.S. maintains a strong, capable merchant fleet when it needs one.