Humans, Systems, and Holism: Human Complexities in Healthcare Fieldwork

Written for the Humanitarian Engineering, Science & Technology (HEST) Student Blog to support ongoing research sponsored by the Evans Family Fellowship in Humanitarian Engineering.

Ethan Copple

4/14/20254 min read

In recent years, it’s become clear that many of the world’s most urgent challenges, ranging from healthcare access to supply chain resilience, cannot be solved through linear thinking or isolated fixes. These are complex systems problems, shaped by tangled networks of infrastructure, human behavior, policy, and economics. Yet, much of the traditional research and intervention in these areas continues to rely on reductionist approaches that break problems into parts, often missing the forest for the trees. My research begins with a different premise: that to meaningfully understand and improve systems like healthcare, we must analyze how their components interact - dynamically, socially, and structurally or simply, holistically.

To explore how to holistically study healthcare delivery, I conducted field research in the Province of Buenos Aires, Argentina with the support of the Evans Family Fellowship. My research uses a transdisciplinary methodology that blends systems engineering, anthropology, and network analysis. This allowed me to study healthcare delivery not just as a question of service provision, but as a complex, adaptive system shaped by policy constraints, infrastructure, and human relationships. Understanding a healthcare system holistically requires hearing from the people who experience it, those navigating and working through its breakdowns, workarounds, and informal structures: patients and providers. Thus, interviews were essential for uncovering how policies and infrastructure play out on the ground, revealing dynamics that available data doesn’t convey.

Fieldwork in Argentina

As a two-time Evans Family Fellow in Humanitarian Engineering, I’ve now traveled to Argentina three times for a total of over six months and conducted over 230 interviews in the Province of Buenos Aires with a mix of providers and patients.

Doing research and fieldwork in another country makes for some interesting conversations. Pretty much everyone who goes to Argentina spends most of their time in the city of Buenos Aires. But, given my work in the rural province, I’ve spent about twice as much time in a single, small farming town of about 10,000 people as I have in the city. The province feels a lot more like my home though. I’m a Kansan, so the large wheat, soy, and sunflower fields that populate the similarly flat plains feels quite comfortable to me. The cowboys wear different hats and pants in Argentina, but their role in tending cattle, navigating rural economies, and shaping local identity feels surprisingly similar to Kansas cowboys. Without context, photos of grain elevators and cow pastures could easily be mistaken for scenes from the Great Plains. That familiarity helped me build trust and connect with people during interviews, giving us a shared language of land, work, and place.

Illustrative Narratives

I wanted to share some quick narratives from my fieldwork that highlight the value of anthropological approaches to a holistic study of healthcare. As you’ll note while reading them, a ‘mathematically optimized’ systems approach would fail to address these very human aspects of success and failure in healthcare access.

In many interviews, one theme emerged again and again: trust is not a given in healthcare systems. It must be built and maintained. One patient talking to me about how providers build trust said, “They take genuine interest in what's going on in my story… when they're humble enough to admit when they don't know something and refer me elsewhere.” This kind of relational dynamic, grounded in humility and mutual respect, surfaced as a key enabler of access. While most systems models focus on infrastructure or policy, these kinds of interpersonal moments are where access actually happens or fails to.

In one public clinic, a director emphasized the importance of holistic, family-centered care, saying, “The focus here is on trying to change the cycle of the whole family.” This simple statement reflects a profound system's truth: effective care doesn't operate in isolation. It’s entangled with housing, work, and education (i.e., social determinants of health). These insights help to highlight the limitations of engineering-alone interventions and how those interventions need to be embedded in the broader social systems people live within.

And then there are stories that resist categorization, like a woman who came to the clinic with chest pain. After exams showed no biomedical cause, the staff helped her uncover that the pain was rooted in grief, a somatic expression of the unresolved loss of her son. No spreadsheet, diagnostic code, or optimization model could have captured that.

These stories demonstrate why data must be paired with listening, and why complex systems can’t be diagnosed without engaging the people who live inside them.

From Stories to Systems Tools

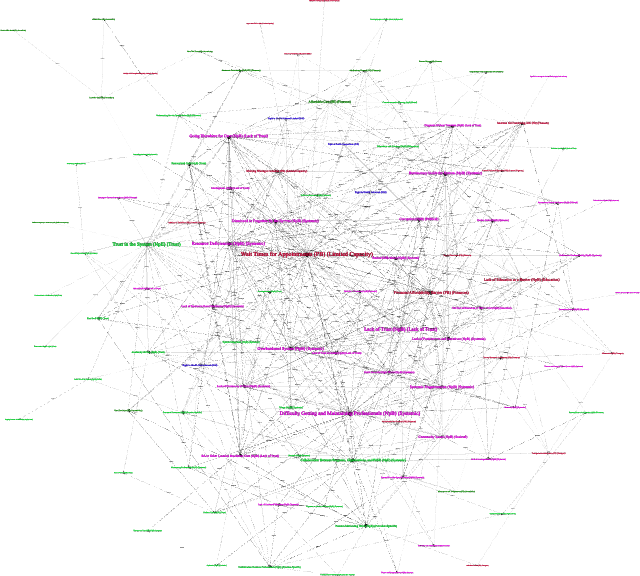

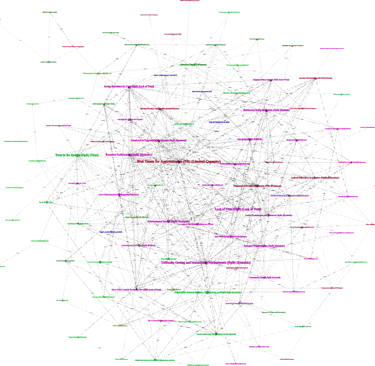

The stories I heard weren’t just anecdotes, they are data points in a larger system. By combining these interviews with structural mapping and systems analysis, I was able to identify and visualize patterns that wouldn’t show up in spreadsheets or charts alone. For example, trust consistently emerged as both a barrier and an enabler, depending on how it was experienced in the clinical setting. In traditional models of healthcare delivery, trust is rarely measured, let alone treated as something that can be strategically cultivated. But in this context, it was one of the most powerful forces shaping access.

Building on these insights, I am developing metrics and visual tools to track not just the presence of barriers, but how they interrelate and change over time. These tools are meant to help healthcare administrators, policymakers, and system designers prioritize interventions based not only on severity or frequency, but on adaptability or how changeable a given barrier really is. The aim is to move from a static list of problems to a dynamic map of possibilities, an approach that supports smarter, more human-centered decision-making.

Beyond Healthcare Access in Argentina

While this work is grounded in healthcare access in Argentina, the approach has far broader implications. The same complexity, intertwined infrastructure, policies, and human relationships, exists in supply chains, other public services, and industrial systems. Systems don’t exist in isolation, and neither should the methods we use to understand and improve them.

I’m deeply grateful to the Evans Family Fellowship for supporting this fieldwork and for recognizing the value of humanitarian research.